New Guidance from the Federal Court regarding Comparative Advertising Claims in Canada

A summary of the findings

After much anticipation, a notable decision concerning comparative advertising claims in Canada was recently issued by the Federal Court of Canada in Energizer Brands, LLC v. Gillette Company, 2023 FC 804. The case dealt with whether the use of comparative performance claim labels and stickers on packaging depreciated trademark goodwill contrary to section 22 of the Trademarks Act, and whether the claims were deceptive, false or misleading in violation of certain unfair competition provisions of the Act as well as of the Competition Act.

Justice Fuhrer of the Federal Court found that statements on Duracell’s packaging using ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX were likely to depreciate the goodwill of Energizer’s registered trademarks, and thus awarded Energizer an injunction against Duracell prohibiting the use of Energizer’s marks and damages in the amount of $179,000. The stickers – which did not use Energizer’s registered trademarks – were found not to depreciate and, as well, were not deemed to be offensive, deceptive, false or misleading contrary to the Trademarks Act and Competition Act.

Background

The dispute between Energizer and Duracell (The Gillette Company, the owner of the DURACELL mark) centered around certain comparative advertising claims found on labels and stickers affixed to DURACELL battery packaging that bore the following statements:

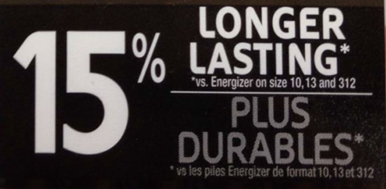

- 15% LONGER LASTING vs. Energizer

- UP TO 15% LONGER LASTING vs. ENERGIZER MAX

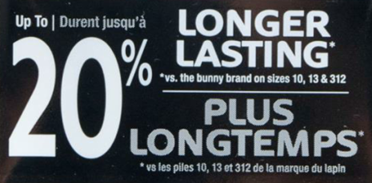

- Up To 20% LONGER LASTING vs. the bunny brand

- Up to 15% longer lasting vs. the next leading competitive brand

|

|

|

|

Section 22 of the Trademarks Act provides that “no person shall use a trademark registered by another person in a manner that is likely to have the effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attaching thereto”. To succeed in a claim for depreciation of goodwill, a plaintiff must meet the following four‑part conjunctive test as described by the Supreme Court of Canada in Veuve Clicquot:

- its registered trademark was used by the defendant with goods or services, regardless of whether they are competitive with those of the plaintiff;

- its registered trademark is sufficiently well known to have a significant degree of goodwill attached to it, although there is no requirement that the trademark be well known or famous;

- the defendant’s use of the trademark was likely to have an effect on that goodwill (in other words, there was a linkage); and

- the likely effect is to depreciate or cause damage to the value of the goodwill.

In the Energizer/Duracell case, both parties accepted that the ENERGIZER trademarks were well known, if not famous and significant goodwill resided in them.

Justice Fuhrer noted that the “use” as required by section 22 was aligned with the manner of use contemplated in section 4 of the Trademarks Act. However, such use does not necessarily have to be employed for the purpose of distinguishing the owner’s products or services from others (i.e., “non-confusing use”).

Duracell’s display of the registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX on the sticker labels of Duracell batteries constituted section 4 non-confusing use. As to whether the use was likely to have an effect on the goodwill and to depreciate or cause damage to its value, Justice Fuhrer noted that the “purpose of putting the Energizer Trademarks on the packaging was to promote the sale of DURACELL batteries by suggesting to consumers that they would get a better result using Duracell’s batteries in the hope of getting a part of the market enjoyed by Energizer”. This was a clear example of a trademark owner’s trademark being “bandied” about, resulting in lost control for the owner and lesser distinctiveness.

Furthermore, the Exchequer Court of Canada in the Clairol decision had already established that damage to goodwill can occur through the reduction of the esteem in which a registered trademark is held, arising from the direct persuasion and enticing of a company’s customers who could otherwise be expected to buy or continue to buy the registered trademark owner’s products if it wasn’t for the third-party statement mentioning the registered trademark.

Following the Clairol decision, Justice Fuhrer found Duracell’s use of the comparative advertising stickers with the ENERGIZER marks depreciated the goodwill of Energizer’s trademarks for the express purpose of taking away custom enjoyed by Energizer and persisted in it.

With respect to the comparative performance advertising claim “Up To 20% LONGER LASTING vs. the bunny brand”, Justice Fuhrer found that while the phrase “the bunny brand” was capable of evoking an image of a bunny that functions as a trademark (that is Energizer’s iconic ENERGIZER bunny, subject to several trademark registrations), hurried consumers were unlikely to pause long enough and think of Energizer’s character when seeing this phrase. Consumers had to take an extra mental step or steps when confronted with the indirect phrase “the bunny brand”, as compared to the more direct trademarks, ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX. In the absence of any primary data or survey evidence of consumer reaction to Duracell’s sticker mentioning the bunny brand, Justice Fuhrer was unable to find a requisite link to support a section 22 claim. This finding suggests that survey evidence might be highly valuable to establish linkage, particularly in situations where registered trademarks are not directly used and/or shown in comparative advertising claims.

|

|

With respect to the “Up to 15% longer lasting vs. the next leading competitive brand” statement, Justice Fuhrer agreed with Duracell that this use was not sufficiently similar to any of Energizer’s trademarks so as to evoke one of them to a hurried consumer. In other words, consumers would not recognize this phrase to mean Energizer’s trademarks based on a first-impression test. Justice Fuhrer noted that the question was whether consumers would link “the next leading competitive brand” to Energizer’s trademark, not whether the consumer knows who “the next leading competitive brand” is and is familiar with its trademarks.

False or Misleading Claims

With regards to whether the claims on the stickers were deceptive, false or misleading, Justice Fuhrer found that the comparative advertising claims complied with the unfair competition (deceptive and false or misleading) provisions of the Trademarks Act, as well as section 52(1) of the Competition Act.

Subsection 52(1) provides that “[n]o person shall, for the purpose of promoting … the supply or use of a product … knowingly or recklessly make a representation to the public that is false or misleading in a material respect.” Justice Fuhrer summarized and adopted principles earlier articulated by the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia for determining what is false or misleading. The principles included that the general impression of the advertisement must be determined, in both its literal meaning and its context, the misleading advertising must be material in that it would have a pertinent, germane or essential effect upon a consumer’s buying decision, and even advertisements which “push the bounds of what is fair” are not necessarily misleading in a material way. From the Supreme Court of Canada decision of Richard v. Time, the general impression of the advertisement is taken of the entirety of the advertisement and by the relevant consumer who is credulous and inexperienced.

Given that no primary data or a consumer survey about the general impression of the sticker claims were provided in evidence, Justice Fuhrer relied on a common-sense approach and considered the battery testing evidence presented by both parties in assessing the performance claims, while noting that Energizer’s battery testing expert did not have access to Energizer’s testing data.

With respect to Duracell’s sticker claiming “15% LONGER LASTING vs. Energizer on size 10, 13, and 312” for hearing aid batteries, Justice Fuhrer concluded that the lack of a disclaimer on the sticker was significant in assessing whether it was misleading or unfair. While Energizer argued the claim was untrue, Duracell’s evidence suggested a reasonable basis for the claim; Justice Fuhrer accordingly did not find the sticker per se false or misleading in a material way, particularly given the absence of any increased Duracell sales due to the sticker alone.

The literal claims of the remaining stickers were held by Justice Fuhrer to be clear and represented that DURACELL batteries would last “up to” the stated longevity. The expert evidence presented by Duracell formed a reasonable basis to support the performance claims on the stickers, and thus the claims were not deemed false or misleading in a material respect. Further, the presence of disclaimers such as “up to” and “results vary by device and usage patterns” tempered consumer expectations in the circumstances. As there was a reasonable basis for Duracell to make the performance claims, the claims were not deemed to be false or misleading in a material respect, especially due to the absence of evidence showing a rise in Duracell’s sales or lost sales for Energizer as a result of the stickers.

Takeaways

While some may perceive this Energizer/Duracell decision to be overly restrictive and a hindrance to free competition, the decision confirms the earlier Clairol decision and reinforces that the use of third-party trademarks in comparative advertising claims remains risky in Canada.