2023 Year in Review: Key Canadian Trademark Developments

Throughout 2023 (and into the beginning of 2024), the Canadian Trademarks Office, the Trademarks Opposition Board, the Québec legislature and Canadian Courts continued to provide change and guidance to Canadian trademark practitioners in several noteworthy developments. The following represents a summary of our “top picks”.

Trademark Examination Delays are About to Improve (for Some Applications)

On January 1, 2024, the Trademarks Office amended certain of its trademark service standards. Most notably, the Office committed to significantly faster examination of domestic trademark applications.

Previously, there were no service standards tied to examination, only to the issuance of a filing notice within 2 weeks of receipt of a compliant electronic application.

With the changes, for domestic trademark applications (not Madrid Protocol applications) filed through the Trademarks Office’s online system, the Office has committed to sending a first action (approval or first examiner’s report) within:

- 18 months from the filing date of a domestic electronic application filed using the pre-approved list of goods and services and payment of the prescribed fee; and

- 28 months from the filing date of a domestic electronic application that is filed without using the pre-approved list of goods and services and payment of the prescribed fee.

For some time, examination for applications filed using only pre-approved goods and services from the Office’s Goods and Services Manual has been “accelerated” (currently to 20 months). However, for applications filed not using pre-approved goods and services (or featuring a mixture of pre-approved and non pre-approved goods and services), the new service standard of 28 months represents an improvement of more than 2 years from the current turnaround time of 55 months.

With the onboarding of more than a hundred new trademark examiners, hopefully, the Trademarks Office will be able to meet these new service standards, without sacrificing the quality of examination, and also address delays in secondary examination (for which there are no current services standards).

Trademark Fees Increase for 2024

2024 brings fee adjustments applying to the majority of the fees for the Trademarks Office’s trademark services, including filing applications and renewing registrations. The change maintained the current fee structure, but increased most fees by 25%. Below are some of the fee increases:

| Filing Fees* | Old fee | 2024 fee |

| 1st class: | $347.35 | $458.00 |

| Each additional class: | $105.26 | $139.00 |

| Renewal Fees* | ||

| One class: | $421.02 | $555.00 |

| Each additional class: | $131.58 | $173.00 |

| Assignments/Ownership Transfers | ||

| Filing fee | $100.00 | $125.00 |

| Statement of Opposition | ||

| Filing fee | $789.43 | $1,040.00 |

| Extensions of Time (where applicable) | ||

| Filing fee | $125.00 | $150.00 |

| Request S. 45/Expungement Proceedings | ||

| Filing fee | $421.02 | $555.00 |

| Registration Fee | ||

| Filing fee | $210.51 | $277.00 |

*for online filings

The government fee adjustments were stated, at introduction, as allowing the Trademarks Office to address structural deficits, account for inflation, and keep pace with its international counterparts. Canada’s government fees had not undergone comprehensive review since 2004, and Canada’s trademark registration fees have generally been lower than comparable IP offices in the US and EU.

Extensions of Time in Trademark Opposition and Non-use Cancellation (Section 45) Proceedings Shortened

On December 1, 2023, the Trademarks Opposition Board implemented changes in practice on extensions of time available in trademark opposition proceedings and in non-use cancellation (section 45) proceedings. These changes are consistent with Opposition Board changes already implemented that have seen proceedings move from commencement to hearing more quickly and decisions issued faster than before. With these changes, the pace of proceedings will further quicken.

In opposition proceedings, the reductions:

- extension of time available to file a Statement of Opposition reduced from four to two months;

- extension of time to file a Counterstatement reduced from two months to one month;

- extension of time for either party to submit evidence reduced from three to two months;

- extension of time to submit Opponent’s reply evidence reduced from four months to one month;

- extension of time for filing Written Representations reduced from two months to one month;

- requests for a cooling off period (a longer extension of time to allow for settlement discussions or mediation) reduced from nine to seven months;

- cross-examination period reduced from four to two months.

In non-use cancellation (section 45) proceedings, the reduction:

- extension of time available for a trademark registration owner to serve and file its use evidence reduced from four to two months.

Some Clarity on Québec’s Bill 96

In 2023, trademark practitioners (and Québec businesses) expected the Québec government to publish draft regulations to amend the existing regulations respecting the language of commerce and business, under Québec’s Charter of the French Language, following the enactment of Bill 96. Publication did not come in 2023, but did on January 10, 2024.

Some of the main highlights of the published draft regulations include:

- softening the new requirements for text on products/packaging, as opposed to public signage, that required that any non-French trademark had to be registered by June 1, 2025, to be exempt, by proposing that pending applications will be sufficient to qualify for the exception;

- confirming that non-French generic/descriptive terms within a registered trademark on a product that will have to also appear in French cannot be more prominent or be available in more favourable conditions than their French counterparts; and

- granting a phase-out period for products that do not comply with the new requirement, until June 1, 2027, provided that the product was manufactured before June 1, 2025, and no French version of the mark was registered at the date of coming into force of this Regulation.

This infographic from the Québec government on the application of the draft regulations to products assists in understanding the proposed changes (where all text, but the BESTSOAP trademark, appears in French in the same size as English text):

As well, the draft regulation replaces the “sufficient presence of French” requirement that came into force in 2016 for store-front signage (which could be smaller in size than the non-French trademark) and repeals and replaces the current regulation defining the scope of the expression “markedly predominant”, with a more stringent requirement. For instance, the presumption that the size of characters in French text or space allocated to French text being twice as large as other languages would be considered as markedly predominant, without taking into account the non-French trademark, has been replaced by the strict requirement that the French text will have to be at least twice as large and as visible as the non-French text, taking into account the non-French trademark. In other words, where there is non-French text on store-front signage, including a registered trademark, French will have to occupy at least 2/3 of all writing on that signage.

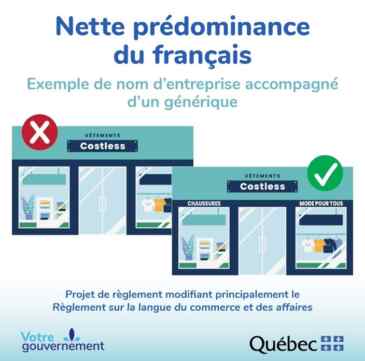

These infographics from the Québec government on the application of the draft regulations to signage assist in understanding the proposed changes (where, in the first example, the generic appears twice as large as the trademark; and, in the second and third examples, the generics are smaller than the non-French trademark/trade name but, with the added French slogans, the total of the French text seems like twice the size of the non-French trademark/trade name):

Unfortunately, there are still uncertainties that the draft regulation has not addressed, such as:

- the definition of a “medium permanently attached to the product”; and

- it does not mention clearly descriptive trademarks that have become distinctive through use and registration under s. 12(3) of the Trademarks Act.

Further changes may come after the consultation period on the published draft regulations ends.

Comparative Advertising Claims Remain Risky

Energizer Brands, LLC v. Gillette Company, 2023 FC 804 gave a fresh take on a much-cited 1968 decision addressing comparative advertising claims. Specifically, the decision considered whether the claims made depreciated trademark goodwill, and, as well, were deceptive, false or misleading in violation of certain unfair competition provisions of the Trademarks Act, as well as of the Competition Act.

Justice Fuhrer of the Federal Court found that certain statements on Duracell’s packaging using Energizer’s ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX trademarks were likely to depreciate Energizer’s goodwill in its registered trademarks, and thus awarded Energizer an injunction against Duracell prohibiting the use of Energizer’s marks, together with damages in the amount of $179,000. Other statements not using the marks, but using the “bunny brand”, were not found to depreciate, owing to a lack of evidence of consumer reaction to the “bunny brand” use.

The dispute between Energizer (the owner of the ENERGIZER marks) and Duracell (the Gillette Company, the owner of the DURACELL mark) centred around certain comparative advertising claims found on labels and stickers affixed to DURACELL battery packaging that bore the statements: “15% LONGER LASTING vs. Energizer”; “UP TO 15% LONGER LASTING vs. ENERGIZER MAX”; “Up To 20% LONGER LASTING vs. the bunny brand”; and “Up to 15% longer lasting vs. the next leading competitive brand”.

Section 22 of the Trademarks Act provides that “no person shall use a trademark registered by another person in a manner that is likely to have the effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attaching thereto.” To succeed in a claim for depreciation of goodwill, a plaintiff must meet the following four‑part conjunctive test as described by the Supreme Court of Canada in Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v. Boutiques Cliquot Ltée:

- its registered trademark was used by the defendant with goods or services, regardless of whether they are competitive with those of the plaintiff;

- its registered trademark is sufficiently well known to have a significant degree of goodwill attached to it, although there is no requirement that the trademark be well-known or famous;

- the defendant’s use of the trademark was likely to have an effect on that goodwill (in other words, there was a linkage); and

- the likely effect is to depreciate or cause damage to the value of the goodwill.

In this case, satisfying the second test element, both parties accepted that the ENERGIZER trademarks were well-known, if not famous, and significant goodwill resided in them.

Justice Fuhrer noted that the “use” as required by section 22 was aligned with the manner of use contemplated in section 4 of the Trademarks Act. However, such use does not necessarily have to be employed for the purpose of distinguishing the owner’s products or services from others (i.e., “non-confusing use”).

Duracell’s display of the registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX on the sticker labels of Duracell batteries constituted section 4 non-confusing use. As to whether the use was likely to have an effect on the goodwill and to depreciate or cause damage to its value, Justice Fuhrer noted that the “purpose of putting the Energizer Trademarks on the packaging was to promote the sale of DURACELL batteries by suggesting to consumers that they would get a better result using Duracell’s batteries in the hope of getting a part of the market enjoyed by Energizer”. This was a clear example of a trademark owner’s trademark being “bandied” about, resulting in lost control for the owner and lesser distinctiveness.

Furthermore, in the 1968 decision in Clairol International Corp. et al v. Thomas Supply and Equipment Co, the Exchequer Court of Canada had already established that damage to goodwill can occur through the reduction of the esteem in which a registered trademark is held, arising from the direct persuasion and enticing of a company’s customers who could otherwise be expected to buy or continue to buy the registered trademark owner’s products if it wasn’t for the third-party statement mentioning the registered trademark.

Following the Clairol decision, Justice Fuhrer found Duracell’s use of the comparative advertising stickers with the ENERGIZER marks depreciated the goodwill of Energizer’s trademarks for the express purpose of taking away custom enjoyed by Energizer and persisted in it.

With respect to the comparative performance advertising claim “Up To 20% LONGER LASTING vs. the bunny brand”, Justice Fuhrer found that while the phrase “the bunny brand” was capable of evoking an image of a bunny that functions as a trademark (that is, Energizer’s iconic ENERGIZER bunny, subject to several trademark registrations), hurried consumers were unlikely to pause long enough and think of Energizer’s character when seeing this phrase. Consumers had to take an extra mental step or steps when confronted with the indirect phrase “the bunny brand”, as compared to the more direct trademarks, ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX. In the absence of any primary data or survey evidence of consumer reaction to Duracell’s sticker mentioning the bunny brand, Justice Fuhrer was unable to find a requisite link to support a section 22 claim. This finding suggests that survey evidence might be highly valuable to establish linkage, particularly in situations where registered trademarks are not directly used and/or shown in comparative advertising claims.

With regard to whether the claims were deceptive, false or misleading, Justice Fuhrer found that the comparative advertising claims complied with the unfair competition (deceptive and false or misleading) provisions of the Trademarks Act, as well as section 52(1) of the Competition Act.

Subsection 52(1) provides that “[n]o person shall, for the purpose of promoting … the supply or use of a product … knowingly or recklessly make a representation to the public that is false or misleading in a material respect.” Justice Fuhrer adopted principles earlier articulated by the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia for determining what is false or misleading. Justice Fuhrer also applied the findings of the Supreme Court of Canada on the general impression of an advertisement.

The principles included that the general impression of the advertisement must be determined, in both its literal meaning and its context, the misleading advertising must be material in that it would have a pertinent, germane or essential effect upon a consumer’s buying decision, and even advertisements which “push the bounds of what is fair” are not necessarily misleading in a material way.

Given that no primary data or a consumer survey about the general impression of the sticker claims were provided in evidence, Justice Fuhrer relied on a common-sense approach and considered the battery testing evidence presented by both parties in assessing the performance claims, while noting that Energizer’s battery testing expert did not have access to Energizer’s testing data.

With respect to Duracell’s sticker claiming “15% LONGER LASTING vs. Energizer on size 10, 13, and 312” for hearing aid batteries, Justice Fuhrer concluded that the lack of a disclaimer on the sticker was significant in assessing whether it was misleading or unfair. While Energizer argued the claim was untrue, Duracell’s evidence suggested a reasonable basis for the claim; Justice Fuhrer accordingly did not find the sticker per se false or misleading in a material way, particularly given the absence of any increased Duracell sales due to the sticker alone.

The literal claims of the remaining stickers were held by Justice Fuhrer to be clear and represented that DURACELL batteries would last “up to” the stated longevity. The expert evidence presented by Duracell formed a reasonable basis to support the performance claims on the stickers, and thus the claims were not deemed false or misleading in a material respect. Further, the presence of disclaimers such as “up to” and “results vary by device and usage patterns” tempered consumer expectations in the circumstances. As there was a reasonable basis for Duracell to make the performance claims, the claims were not deemed to be false or misleading in a material respect, especially due to the absence of evidence showing a rise in Duracell’s sales or lost sales for Energizer as a result of the stickers.

Trademark Licensing Control Remains a Question

Milano Pizza Ltd. v. 6034799 Canada Inc., 2023 FCA 85 was the first of two 2023 decisions in which the Federal Court of Appeal considered the issue of “control” under section 50 of the Trademarks Act. Under that section, use of a trademark by a licensee is deemed to count as the owner’s use if the owner has “control of the character or quality of the goods or services” with which the licensee uses the mark.

Milano Pizza was an appeal of a decision that dismissed the appellant’s action for trademark infringement. The trial judge canceled the appellant’s trademark registration on the basis that the registered mark was not distinctive – the appellant had failed to show sufficient control over use of the mark by “licensees” to be deemed the owner’s use under section 50.

The appellant argued that the judge erred in assessing the sufficiency of control, saying that a trademark owner should be able to determine the appropriate manner and extent of control over the character or quality of the associated goods or services. Specifically, the appellant argued that it had sufficient control through a requirement that licensees purchase their pizza ingredients, pizza boxes and drinks from authorized distributors, and through a geographical region limitation on its licensees. The trial judge had found these requirements insufficient to establish the requisite control to trigger the section 50 deeming provision.

The Federal Court of Appeal found no error. It considered that the appellant’s position would mean that Courts are not permitted to determine the meaning of “control” in section 50, and must take the trademark owner’s word that they assert control over the final product or service. This position was considered not compatible with the rationale behind section 50, which is to ensure consistent quality across all products or services bearing a particular trademark – control over the finished product or service was held to be required. The Federal Court of Appeal commented that “it would make a mockery of s. 50(1)” if any type or degree of control was acceptable.

Seven months later, the Federal Court of Appeal again considered the issue of “control” in Dragona Carpet Supplies Mississauga Inc. v. Dragona Carpet Supplies Ltd., 2023 FCA 228. The case involved two separate carpet supply businesses that were owned and operated by an extended family – one with stores in Mississauga, the other with stores in Scarborough – both of which used the trademark DRAGONA. When the Scarborough business opened a location in Mississauga that displayed the DRAGONA trademark, the Mississauga business sought an injunction. The action was dismissed after summary trial, and the Mississauga business appealed.

The appellant argued on appeal that Dragona Scarborough did not exercise adequate control over the character or quality of Dragona Mississauga’s goods or services as required by section 50(1) — the appellant relied on the Court’s decision in Milano Pizza in support.

The Federal Court of Appeal declined to overturn the trial judge, but acknowledged a tension between the two decisions with its comment that the trial judge’s reasons “swim dangerously close” to committing the error described in Milano Pizza (of taking the trademark owner’s word that they assert control over the final product or service). The Federal Court of Appeal considered the rather thin licensing evidence as sufficient to establish control, as the judge’s decision on the existence of an oral licence was based on his assessment of the entire history of business dealings between the parties.

The trial judge found that between 2012 and 2021 there was no reason for Dragona Scarborough to take issue with Dragona Mississauga’s use of the mark. Further, the close family relationship, assurances that the Mississauga business was planning to phase out use of the mark, the evidence that the Scarborough owner visited and “kept an eye” on the Mississauga business, and the fact that the vast majority of items in the two stores were identical, all were said to give context to the degree of evidence of control to be expected in the circumstances.

Dragona Scarborough did not need to control every aspect of the Mississauga business operations in order to control its use of the DRAGONA trademark – the trial judge was willing to find that it would have stepped in had it taken issue with how the appellant was using the mark. Because there was a licence in place, goodwill earned by Dragona Mississauga during the 2012 to 2021 period was deemed to have accrued to Dragona Scarborough. Accordingly, Dragona Mississauga could then not establish that Dragona Scarborough was passing off when it sought to enter the Mississauga market.

The inevitable conclusion that follows from a study of the Federal Court of Appeal’s 2023 decisions in Milano Pizza and Dragona, is, as the Court stated in Dragona, that “control is a heavily fact dependent determination.”

Bad Faith Considered

In Cheung’s Bakery Products Ltd. v. Easywin Ltd. (2023 FC 190), two Chinese baked goods manufacturers entered, for a second time, in a trademark tussle over their respective trademark rights for marks containing the same Chinese characters. Easywin’s trademark registrations were ultimately expunged on the basis (i) that Easywin was not entitled to secure its registrations because the parties’ marks contained the same Chinese characters and (ii) that the Easywin registrations had been filed in bad faith.

Regarding the issue of entitlement, when determining the probable confusion between the trademarks that included the same two Chinese characters, the Court emphasized that the evaluation of confusion should be considered from the perspective of the likely purchaser of the products or services linked with the trademarks, in the particular market where they are offered. Given that the products in question were aimed at the “Chinese-Canadian market”, the Court recognized the likely buyer of these products as “an average, casual Canadian consumer who can read and understand Chinese characters, albeit with varying degrees of fluency” and thus appreciate the similarity in sound and idea suggested.

Expert evidence was proffered by both parties on the question of Chinese character fluency and the general impression of a trademark containing Chinese characters on the mind of a consumer within the Chinese-Canadian market. CBP’s expert simply stated that the last two characters in Easywin’s marks were identical to the first two in CBP’s, translating to “Anna” in both Mandarin and Cantonese. Easywin put forward a marketing and consumer behaviour expert, who posited that the average Canadian consumer would perceive non-Latin characters primarily as designs and not as word marks. This view, however, was limited by the assumption that the average Canadian cannot understand Chinese characters.

The Court focused on Easywin’s failure to counter the Court’s previous finding in Saint Honore Cake Shop Limited v Cheung’s Bakery Products ltd., 2013 FC 935 (aff’d 2015 FCA 12) that concluded a substantial portion of CBP’s consumers can understand Chinese characters (this previous case was between CBP and Easywin’s operating company, Saint Honore). CBP presented similar evidence to the evidence it filed in the earlier case, highlighting that a majority of its customers are of Chinese origin and understand Chinese to some degree – conclusions based on an informal survey conducted by CPB and CPB’s operation manger’s long-term observations. Additionally, the Court was swayed by fact that both CBP’s Easywin’s marketing efforts and product packaging predominantly featured Chinese characters, suggesting that the parties mutually expected a significant portion of their customers, including those in Canada, to read and understand Chinese.

In short, the Court concluded the marks were similar given that relevant consumer would be one who can read and understand the Chinese characters, and thus recognize the similarities in transliteration (sound) and translation into English (idea), in addition to the obvious similarities in appearance. This finding of similarity, in addition to the fact that the parties’ goods and services related to baked goods and that CBP had earlier and more extensive use, led the Court to conclude there was a likelihood of confusion.

On the issue of bad faith, the Court thoroughly examined the context and history between the two competing bakery businesses and their respective trademarks, as this trademark dispute was not the parties’ first rodeo. Central to the bad faith analysis was the acknowledgment of Easywin’s awareness of CBP’s existing trademarks and their shared target market. Easywin is a holding company of the Saint Honore operating company, the later being the party whose marks were expunged by CBP in the 2013 decision. The Court emphasized that Easywin was familiar with CBP’s business and trademarks due to their direct competition in the bakery goods sector and notably the previous dispute involving similar issues between CBP and Saint Honore, indicating a clear awareness on Easywin’s part of CBP’s branding and market presence. The Court found that at the time of filing the trademark applications, Easywin knew that they targeted the same customer base and sold similar types of bakery-related goods and services as CBP. Given this knowledge, Easywin’s decision to proceed with the trademark applications involving similar Chinese characters was seen as a deliberate disregard of the potential for confusion and conflict with CBP’s already established trademarks. This behaviour was deemed indicative of bad faith.

Bad Faith Further Explored

The Application for RITZ YACHTS at issue in this opposition proceeding (The Ritz-Carlton Hotel Company, L.L.C. and Ritzyachts Inc., 2023 TMOB 153) was refused registration on technical grounds under the Trademarks Act as it read prior to June 2019 – before the introduction of an express bad faith ground – but which are of interest to the consideration of the bad faith ground. The technical grounds were that the Applicant did not use its mark as claimed in the Application (section 30(b) of the pre-June 2019 Act) and did not intend to use the RITZ YACHTS mark at the date the Application was filed (section 30(e)).

In support of the section 30(e) ground (the lack of intention to use the mark), the Opponent proffered a short excerpt from cross-examination where the Applicant admitted to not being in the business of “selling yachts or boats” and to not intending to sell boats in the future. The Hearing Office found this admission on cross-examination to both satisfy the Opponent’s “light” initial evidential burden to put this opposition ground into issue, and, in the absence of any evidence from the Applicant to show otherwise, render this ground of opposition successful with respect to the proposed-use goods “yachts” and “custom manufacture of yachts”.

On the section 30(b) ground (attacking the claim of “use” in the Application), the Hearing Officer found the Applicant’s refusal on cross-examination to answer “proper questions concerning the date and scope of use of the Mark” were sufficient to put this ground into play. Moreover, although the Applicant did submit some evidence, there was “no clear description” “of any instance in which any of the services at issue were actually performed or advertised during the relevant period”—there were no sales or revenue figures; invoices were issued to the Applicant, not from the Applicant to third parties for any services rendered; and no evidence showed how the Mark would have been displayed in the performance of the claimed services. The mere presence of the Mark on business cards, without more, precluded a conclusion that the business cards “constitute[] advertisement” of the specific applied-for services. Similarly, evidence showing the Applicant had no active website on the relevant dates, contributed to the finding the Applicant failed to show it continuously used its mark with the applied-for services as of the date claimed in the Application.

In addition to the opposition grounds, the decision addressed the scope of cross-examination (and the related issue of improper refusals). The Hearing Officer referred to the Board’s decision in Coca‑Cola Ltd v Compagnie française de Commerce International COFCI S.A., (1991), 35 CPR (3d) 406 (TMOB) at 412–413, which characterized cross-examination on opposition as being both part of an “inter partes” proceeding and “in the public interest”, such that there is an “extended scope of cross-examination in opposition proceedings” entitling the cross-examiner to asked questions about related issues, such as the applicant’s date of first use of its trademark. Consequently, in Ritz Yachts, the Hearing Officer drew negative inferences from the affiant’s refusal to answer questions about the Applicant’s use of the mark on the basis that the questions were not “within the scope of his affidavit”.

Whack-a-mole Counterfeit Luxury Goods Case Attracts a Sympathetic Rolling Order

In Burberry Limited v. Ward, 2023 FC 1257, Justice Walker of the Federal Court canvassed, in fashioning her order, the different types of injunctive and monetary relief that successful rightsholders might be able to obtain in what the plaintiffs and Justice Walker called “whack-a-mole” cases.

The Plaintiffs – Burberry and Chanel – are very well-known sellers of luxury fashion goods. In 2021, they became aware that an individual in Canada was importing and selling counterfeit Burberry and Chanel branded clothing and fashion accessories. As described by Justice Walker, despite the individual’s initial agreement to cease, she continued to import and sell counterfeit products through a changing and expanding online presence using multiple names, aliases and Facebook pages.

After finding, inter alia, trademark infringement, passing off and depreciation of goodwill, Justice Walker granted an injunction, an order for the delivery up and destruction of the goods, and orders requiring the defendants to identify the suppliers of the goods and prohibiting third parties with notice of the judgment from assisting the defendants. Justice Walker went further by granting an order requiring third parties to provide information regarding the defendants’ infringing activities, provided the plaintiff brought an informal ex parte motion. In addition, Justice Walker granted a rolling order to address the defendants’ persistent attempts to avoid detection through frequent name changes. Finally, each plaintiff received damages for trademark infringement in the amount of $197,000, while Burberry received $120,000 in statutory damages for copyright infringement and $100,000 in punitive damages.

Past Examination “Errors”, and the Ineffectiveness of Consent Agreements

The Federal Court of Appeal (Tweak-D Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General), 2023 FCA 238) upheld a decision of the Trademarks Registrar, made during prosecution, to refuse registration of the mark TRIBAL CHOCOLATE on the basis of section 12(1)(d) that the subject mark was likely to be confusing with the registered mark TRIBAL. In doing so, the Court canvassed key issues relating to several factors that could affect the “likelihood of confusion” analysis, including (a) previously registered trademarks, (b) the State of the Register; and (c) consent agreements. The Court also touched on the standard of review on appeals from decisions taken by trademark examiners confirming they are “statutory appeals” subject to review for palpable and overriding error on questions of mixed fact and law, and for “correctness” for questions of law.

On the “likelihood of confusion” analysis, the Court confirmed that “it is generally irrelevant that a given mark may have been registered in the past”, such that there was no error or inconsistency between the Examiner’s refusal of the Applied-for mark, and the Office’s grant of registration to a third party mark that the Applicant argued was “closer” to the cited mark than the applied-for mark; that there was no palpable and overriding error in the Examiner’s finding that four registrations and no evidence of use “demonstrate[d] a pattern of registrability of similar marks”; and agreed with the Federal Court and the examiner that a co-existence agreement between the Applicant and the owner of the cited mark “is not dispositive of registrability”, and thus it was open for the Examiner to conclude that such agreement “did not trump the other [likelihood of confusion] factors in subsection 6(5) of the Act”.

On the standard of review, the Court confirmed that appeals of decisions of the Registrar are taken under section 56(1) of the Act and are considered “statutory appeals” subject to the standards of review from Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65 and Housen v. Nikolaisen, 2002 SCC 33 (i.e., “correctness” for questions of law, and “palpable and overriding error” for questions of mixed fact and law). The Court distinguished these types of appeals from those identified by the Supreme Court of Canada in Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada v. Entertainment Software Association, 2022 SCC 30, which involved circumstances where a court and an administrative body have concurrent first instance jurisdiction over a legal issue in a statute.